Article Highlights

Check-in/be-out, or CIBO, systems, are being tried by some transit agencies, particularly in Europe, as they seek to offer hands-free convenience to riders. Agencies need measures to deter fraud if they launch these systems.

Three months after launch, the YANiQ app had received 3,600 downloads across the Android and iOS platforms, the agency reported in late February 2021.

• Stadtwerke Osnabrück

• eos.uptrade

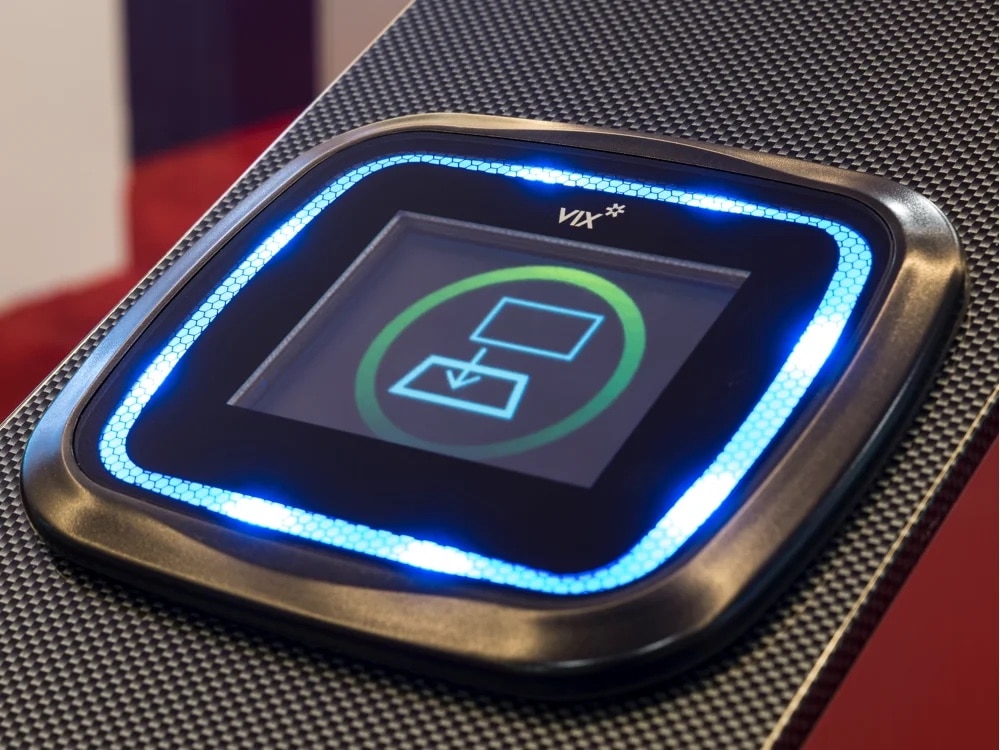

Despite the growing popularity of contactless, NFC and QR-code technologies for electronic fare-collection systems, some transit agencies are experimenting with other technologies to collect fares. That includes Germany’s Stadtwerke Osnabrück, which launched the first check-in/be-out system in the country last October in the city of Osnabrück.