Article Highlights

The Utah Transit Authority received responses from eight vendors to its request for proposal for a new fare system, with five of the vendors submitting lower cost bids than the vendor the authority ended up choosing for the contract, documents obtained by Mobility Payments show.

• Table: UTA Tender–Rank of Bidders

• Table: UTA Price Bids-Breakdown

• Evaluation Score Sheet

• UTA (Utah)

• Scheidt & Bachmann

• Masabi

• Bytemark

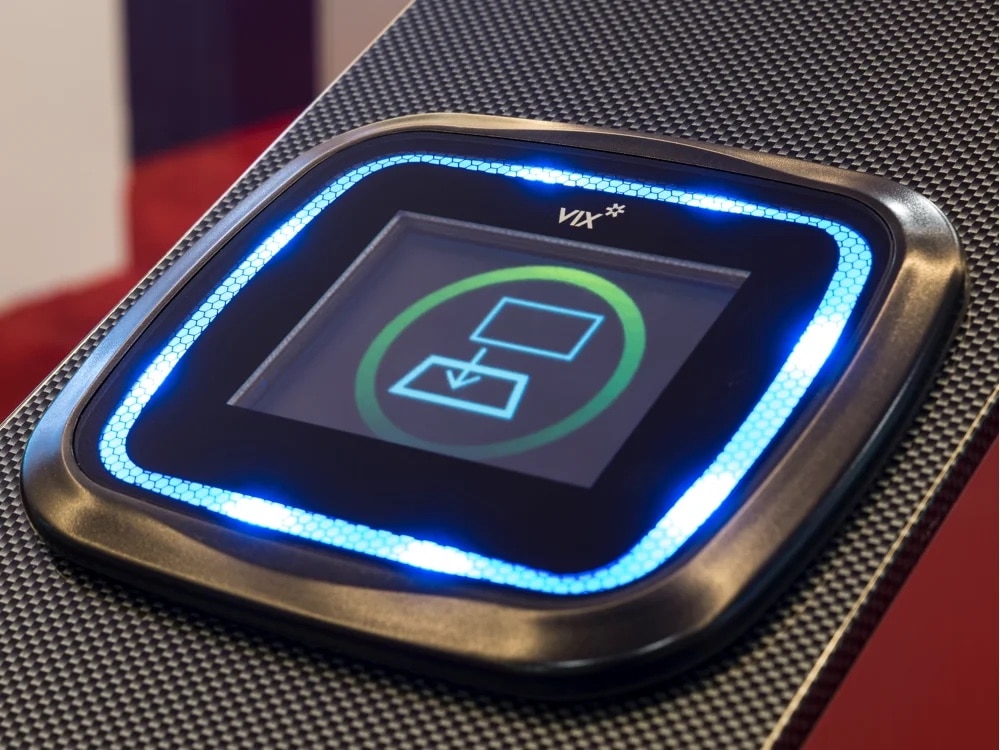

• Vix

• Moovel

• Cubic

• INIT

• Access-IS

• Modeshift

The Utah Transit Authority received responses from eight vendors to its request for proposal for a new fare system, with five of the vendors submitting lower cost bids than the vendor the authority ended up choosing for the contract, documents obtained by Mobility Payments show.