Article Highlights

Boston’s massive account-based ticketing project got a “reset” that extended the rollout schedule to 2024 and increased the vendor contract or contracts by nearly 30% to over $935 million. The revised contract will deal technical challenges, an overly optimistic rollout and implementation schedule and requests for additional functionality.

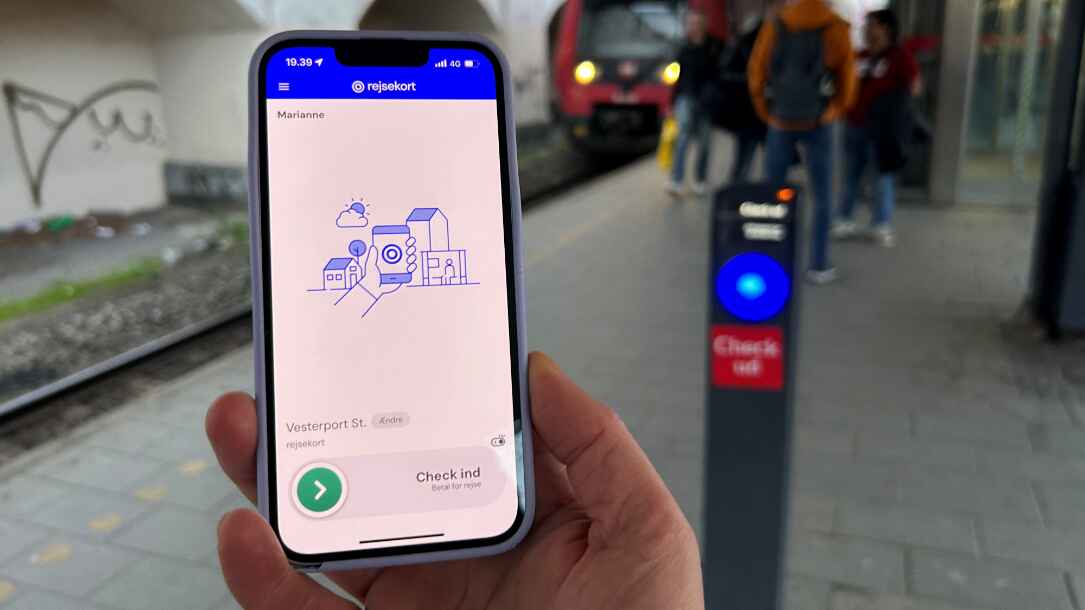

Chart: Growing use of mobile tickets by Boston’s MBTA.

• MBTA

• Cubic Transportation Systems

• John Laing Group

• Masabi

The massive new fare-collection system planned by Boston’s Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, or MBTA, which will include open-loop contactless payments and an expanded closed-loop program, has had trouble getting off the ground. Late last week, the transit agency finalized its “reset” of the project, agreeing to increase the contract by nearly 30% to just over $935 million and to add two more years to the rollout schedule–all in hopes of getting the project back on track.