Article Highlights

Third-party providers are promoting their cloud-based software-as-a-service platforms, hoping to encourage more transit agencies to outsource their fare collection via smartphone apps, especially agencies that still accept cash and paper tickets for fares.

• Table with details on three major SaaS ticketing platforms.

• Bar graph showing growth in mobile ticketing for commuter rail operators in New York.

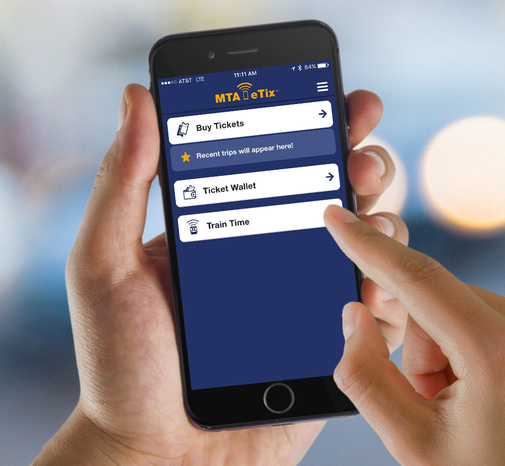

• Metropolitan Transportation Authority

• Masabi

• Cubic

• Token Transit

• Long Island Rail Road

• Metro-North Railroad

• Whatcom Transportation Authority

(This premium article was originally published in May 2020. © Mobility Payments and Forthwrite Media.) As the Covid-19 crisis sows fear among mass transit customers and causes ridership on buses,…